Restructuring U.S. Men's Youth Development

Below is a position paper from Michael Wheeler and Christian Hambleton recommending ways to overhaul and restructure men's youth soccer development in the United States.

Introduction

October 10, 2017, is a date that will never be forgotten for the United States Men’s National Team (“USMNT”) and the United States Soccer Federation (“USSF”). The 2-1 loss at Trinidad & Tobago against an opponent playing its “B” players was the nadir for the USMNT and USSF. Since the loss, a myriad of questions have been asked by supporters and principally focus on the following: “How did we, a global athletic powerhouse with a population of over 323 million people, fail to qualify for the World Cup?” and “What needs to be done to prevent additional future failure?” Searching for these answers should not be limited to the USMNT and its system for identifying national team players. Rather the solution must come from fostering policies and put in place a solid foundation to support the grassroots level of the United States soccer system with the help of USSF to encourage the development and training of future professional and USMNT players.

As it currently stands, youth soccer in America exists as a “pay-to-play” system. Roughly 2/3 of the teams that participate in the USSF Development Academy structure require annual dues, which are approximately $3,000 a year. Combined with travel expenses to league games and tournaments across the country, a year participating in USSF’s Development Academy could cost upwards of $12,000. While there are many people who blame the “pay-to-play” system for the current shambles that soccer in America finds itself, the truth is that the “pay-to-play” system is not going to disappear. The system is engrained in the fabric of America’s capitalistic system. Instead of fighting the current system, a new system must be developed that synthesizes the “pay-to-play” system with training compensation and solidarity mechanism payments, thus permitting “pay-to-play” but also enabling and incentivizing the identification and development of youth players regardless of the players socioeconomic background.

Youth Development in England and France

In England, the Football Association (“FA”) has 21 talent reporters (part-time scouts) for the men’s game. These scouts are both phase (age group) and regional specific. They are supported by 4 full-time Talent Identification managers, 3 goalkeeper specialists, and the national team coaches.

In addition, youth academies must pay previous training clubs if they register an academy player. There are factors that must occur for the previous club to be compensated such as having offered an academy contract to the player and it was rejected; or the academy player moved outside of the catchment area of the previous club. However, the FA, Premiership League and English Football League all have youth rules that determine when training compensation is paid to the previous club. Other factors that determine how much training compensation is owed is the age of the player, length of registration at the previous club and between which category the player is moving from. Although the FA has the ultimate responsibility, the Leagues are responsible for their own competitions and rules.

The current training compensation fees in England that must be paid by clubs that sign a player away from a previous club are as follows:

|

Age group of the Academy Player |

Category of the Academy of the Training Club at the relevant time |

Applicable Annual Fixed Fee |

|

Under 9 to Under 11 |

All Categories |

£3,000 |

|

Under 12 to Under 16 |

Category 1 |

£40,000 |

|

Under 12 to Under 16 |

Category 2 |

£25,000 |

|

Under 12 to Under 16 |

Category 3 |

£12,500 |

Time/Distance Rule for Academy Clubs in England.

|

Permitted Recruitment Time/Distance |

|||

|

|

Foundation |

Youth Development |

Professional |

|

Category 1 |

1 hour |

No limit for players engaged in Full Time training mode |

No limit |

|

Category 2 |

1 hour |

1 ½ |

No limit |

|

Category 3 |

1 hour |

1 ½ |

No limit |

|

Category 4 |

N/A |

N/A |

No limit |

Recently, English youth soccer in the men’s game has achieved unprecedented success in the international tournaments in 2017. English FA won U17 and U20 FIFA World Cup, UEFA U17 runner’s up and UEFA U21 semifinalists and Toulon Tournament winners. Some of the recent changes to the English youth soccer system have nurtured this talent. In 2012, the FA implemented a long-term strategy called the Elite Player Performance Plan (“EPPP”) with the aim of developing more and better homegrown players. The EPPP works across three phases, Foundation (U9-U11), Youth Development (U12-U16) and Professional Development (U17-U23). The FA has increased investment in the EPPP regulations and improved the level of coaching and increased the budget of the Talent ID program. The FA has improved the quality of games for youth teams and increased foreign opposition as well as the normal games program.

Biggest issue that the FA faces is that players are not moving through the pathway within their club and lack opportunities to play for their club’s first team. Only 1 out of 3 players are currently English Qualified Players (“EQP”) starting in the Premiership every week. The numbers are even less in the top 6 clubs. FA has identified the need to have more EQP playing in Champions League football.

In France, the French Football Federation (“FFF”) has one “federal” academy called Clairefontaine. In terms of youth development, players between the ages of 13 and 15 are invited to live and train at the 56-acre facility containing 302 beds, 10 soccer fields (7 grass and 3 synthetic), sports science laboratory, games room, library and cinema. After graduating from Clairefontaine, the best youth players will be selected by professional teams to join their academies. Clairefontaine graduates include: Kylian Mbappe, Anthony Martial, Nicolas Anelka, Louis Saha, William Gallas and Thierry Henry. Clairefontaine mainly serves as a training ground for all National teams along with providing a national center for FFF to encourage, demonstrate and educate coaches throughout the country on the best coaching and training methods.

The FFF has approximately 10 trainers and scouts that form the Direction Technique Nationale (“DTN”). The DTN is supplemented by the support of Technical Regional Advisors (“CTR”) who are paid by the Ministry of Sports. The CTR is made of hundreds of trainers and scouts who are based throughout France and keep track of over 100 amateur leagues.

The traditional route to becoming a professional for a youth player in France is for his youth coach to alert FFF’s DTN and professional clubs in the area prior to the player’s 13th birthday. Scouts and DTN will propose the youth player to go to a regional “Pole Espoir” before the player enters into a professional academy. There are 15 “Pole Espoir” in France with over 400 players. Every year, half of these players will move onto professional academies. Professional academies have over 2000 players registered this season 2017/18. On average, 16% of these players will sign professional contracts.

Besides the professional academies and the federal academy at Clairefontaine, there are over 856 high schools with 26,000 youth players all over France. These high schools have an agreement from FFF and provide specialized soccer programs and studies. However, 99% of all professional players come from professional academies.

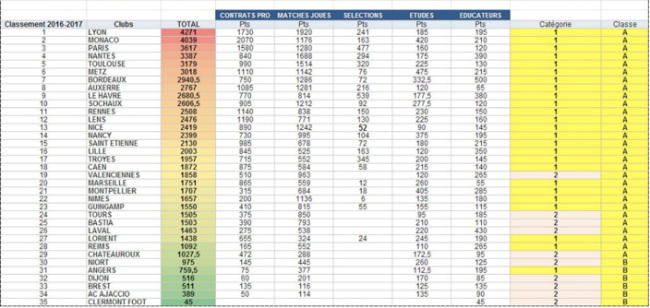

Each year FFF conducts an official ranking of the professional academies by Class (A or B) and then by Category (1 or 2). Depending on the category and class, an academy can welcome certain number of young players and a certain age range.

The ranking is based on:

-Number of players that become professionals

-Matches played

-Selections on the National Teams

-Results in studies

-Qualification of the trainers and educators

The rankings for the professional academies for 2016/17 season was the following:

Restructuring US Youth Development Structure

Given how the FA and FFF have organized their youth development, certain benefits can be adapted to help create a US youth development system that incentivizes player development from the grassroots of youth soccer up through the professional ranks, with the goal of providing the USMNT a more skilled, talented, and deeper player pool than what currently exists.

The first step in the process is organizing the Youth Soccer Club structure to identify youth soccer clubs that instill and promote best practices. While most clubs would like to think that they are a “Tier 1” club, the reality is that very few clubs have the resources and facilities to be granted “Tier 1” classification. Each academy in FA and FFF is held accountable by annual auditing and ranking standards that are the “standard” of player development excellence. Here in the US, there are no objective standards for what makes FC Dallas, or Red Bulls New York, or LA Galaxy academies truly excellent as the reason may be solely due to each academy being located in talent rich catchment areas. By having objectives standards, each academy can evaluate where they need to improve to become a Tier 1 academy or to be ranked as one of the top academies in the US. Under the proposed system, US Youth Soccer Clubs would be structured in a 2 Tier system. Tier 1 would be comprised of clubs that meet the following criteria:

-Field availability

-Infrastructure of the academy

-Education of players

-Quality of coaching staff

-Residency opportunity

-Productivity of graduates to pros or National team selections

Tier 1 clubs don’t necessarily have to be MLS Academy teams. They could be teams with USL affiliation, or even non-MLS affiliated academies like Player Development Academy in Zarephath, New Jersey, which owns its field and facilities. The higher a club’s rating, the more training compensation will be available to that club for promoting its academy players to MLS and professional teams.

Tier 2 clubs would consist of all clubs that do not numerically achieve the ranking to be a Tier 1 club after aggregating the scores from each ranked criteria listed above. A Tier 2 club would not be compensated as much as Tier 1 clubs if their players became professionals, domestically or abroad. Tier 2 clubs would be grandfathered for the current training programs and teams that they have, but any new teams or new age group and catchment area expansions would have to be approved and accredited by the State Association.

To determine the ranking of clubs for the Tier levels, either an independent auditing company could ensure compliance or the USSF could establish an in-house group to audit the youth clubs. The funding for auditing the youth clubs and assessing the effectiveness of the annual rankings should come in partnership from the USSF and MLS as all youth academies should be striving to produce future professional and national team players.

Structuring US Youth Soccer Clubs into tiers offers a tangible and structured system that clearly defines a hierarchy within the realm of the stratified youth soccer system. Youth Soccer Clubs that want to have larger catchment areas and expand into broader age groups must be Tier 1 clubs. There also should be training compensation given to clubs if players are recruited from one youth club to another, domestically, as demonstrated by English FA system. This would prevent the conflicts that exist presently where MLS academies routinely “poach” or “recruit” players from non-affiliated MLS academies. No coach would object if an MLS academy comes and recruits the latest player so long as the prior youth club is compensated for the time and effort put in developing the player.[1] Given the current cost to train a youth player in the US, a Tier 1 club should receive at a minimum $5,000[2] as compensation for each year that the player received training at the prior club. A Tier 2 club should receive at a minimum $3,500 as compensation for each year that the player received training at the prior club.

For players coming from outside of the Tier 1 and Tier 2 clubs, these clubs would still benefit from training compensation and solidarity mechanism payments if their player was recruited abroad. However, to incentivize and raise the training standards within USSF structure, if any players are recruited from non-Tier clubs to Tiered clubs, USSF should implement a policy that allows the lead administrator to either: 1) receive a waiver for additional coaching certifications for their trainers or 2) give the club a stipend for equipment or field time. These incentives would allow these clubs to increase the coaching standards at their clubs, offset the exorbitant costs of training players and hopefully, attract these clubs to become Tier 1 or Tier 2 clubs by USSF investing in their programs.

Centralized clearinghouse to track players and ensure solidarity payments

One of the biggest issues facing this new structured system is organization and regulation. There must be a “clearinghouse” component to the USSF that serves a multi-prong function: 1) player registration and tracking; 2) regulating; and 3) ruling/enforcing.

Player Registration and Tracking

Countries around the world have a player database that allows anyone interested in tracking a player to log onto the database; enter the player’s name; and every team that the player trained with and played for is made available, along with the years that the player was affiliated with each previous club. Such a database and tracking ability makes it easier and more accessible for “Team A” to calculate how much it would cost to sign a player from “Team B.” Additionally, “Team A” would also know if it would owe any additional training compensation to teams besides “Team B” for the time spent developing the player between the ages of 12-23.

We acknowledge that player registration for all youth players in the US between the ages of 12-23 appears to be a daunting task, but in this age of technology, the process can be streamlined by having all existing clubs send their player information to the clearinghouse and have this data entered immediately into a database that can be accessed by anyone in the world given a player’s ITC number or US Player registration number.

Regulation

By having a central registrar, USSF can streamline and facilitate training compensation and solidarity payments to teams when players are signed professionally abroad or if a dispute arises between State Associations regarding the registration of a player from one state to the other. If there are any unclaimed payments for training compensation and solidarity payments, USSF can direct these payments towards programs that help economically disadvantaged communities throughout the U.S. to have access to fields, equipment and coaching.

Having all USSF Youth Soccer players ages 12-23 registered into a single database will allow USSF officials to enforce training compensation and solidarity payments that are owed, and will also allow the tracking of players to ensure that players only transfer between the permitted bi-annual “windows.” Such regulation will prevent players from changing teams whenever they or a new team wants them too, and at the end of each “window”, it will allow for the collection of updated player information, and the calculation of owed training compensation in an efficient manner.

Ruling and Enforcing

It is naïve to think that with players transferring teams and training compensation involved there will not be any disputes. In particular, it is anticipated that there will be challenges to the timing of a transfer; amount of time a club “developed” a player; and amount of training compensation owed and to which teams training compensation is directed.

For these type of disputes, there will be a process for which a club can file an appeal and challenge any issues involved with training compensation and player transfers. These appeals will be filed with the clearinghouse and will be heard by a regional panel composed of 3 independent “judges” that would hold an arbitration hearing where they will hear arguments from both sides. After issuing a ruling, there will be a 15-day window during which time either club can file an appeal that would go before a national panel composed of 3 independent “judges” who are not affiliated with the region from which the case originated. Just with the legal system, the rulings in each of these disputes will be filed with the clearinghouse and will be used as precedent for future panels to refer to and cite in their decisions. The decisions can also be accessed through the database by clubs so that they can review and assess whether or not they have a viable claim to file with the clearinghouse.

Conclusion

Not qualifying for an international tournament or a poor performance on the world stage is not a death sentence for the future of a country’s soccer program. Germany, for example, failed to advance past the group stage at the Euro Cup in 2000 and 2004. Rather than letting its failure torpedo the country’s future success, the German soccer federation reassessed its youth development system; implemented new policy promoting player development and developed a uniformed tactical approach to the game. Since 2004, Germany has finished third at the next two World Cups and most recently won the last World Cup in Brazil.

USSF finds itself at an analogous crossroad as the Germans did in 2004. In response to the USMNT failing to qualify for the 2018 World Cup, the USSF needs to promote pro-grassroots policies and encourage training compensation and solidarity payments within the US to youth clubs.

Youth academy standards for excellence and an objective criteria gives transparency to hierarchy of youth clubs. Additionally, distribution of training compensation and solidarity payments encourages youth clubs to work in concert with each other rather than tearing each other down.

USSF in conjunction with the MLS need to devote resources and coordinate affordable coaching courses for the development of youth soccer in US since both benefit from increasing the talent pool. There also needs to be more talent identification scouts throughout the country helping to identify prospects to the national team and MLS.

Lastly, a central clearinghouse will streamline training compensation and solidarity payments as currently they are not being enforced for arbitrary reasons that have been explored by the authors. This would remove the need for costly litigation and other cases currently before FIFA as USSF would be proactive in structuring its own solidarity payments without the interference from FIFA. A central clearinghouse will also enable the uniform implementation and enforcement of the standards and rulings sought by USSF of its Tier 1 and Tier 2 clubs.

About the Authors

Michael Kaniela Wheeler, Esq. is founder of MAE Agency LLC, an international soccer agency specializing in player and managerial representation throughout North America, Caribbean, South America and Europe, consulting for acquirers and sellers of professional soccer teams, marketing and promoting special events and advising professional leagues on the business of soccer.

Contact: mike@maeagency.com

Christian Wentworth Hambleton, Esq. is a former soccer player at St. Benedict’s Prep and Davidson College, who returned to St. Benedict’s Prep as part of the Varsity Men’s Soccer coaching staff from 2010-2011, before transitioning into litigation defense where he represents clients in various legal matters including general liability, insurance defense litigation, and contract litigation.

Contact: chhambleton@gmail.com

[1] If the player was a “pay-to-play” player, then no compensation would be given to the prior youth club.

[2] FIFA Training Compensation guidelines for CONCACAF compensate Category II clubs $40,000, Category III clubs $10,000 and Category IV clubs $2,000 for every year.

Headlines

- Recruiting Roundup: January 26-February 1

- Professional Signing Tracker: 2025-26

- Tracking Division I Coaching Changes

- 2026 Women's Division I Transfer Tracker

-

ECNL Boys Las Vegas: 2009 Standouts

-

2026 Men's DI Recruiting Rankings: Jan.

-

ECNL Boys Las Vegas: Best of the 2010s

-

Club Soccer Standouts: January 24-25

-

Commitments: From Texas to Utah Tech

-

Player Rankings Spotlight: 2029 Girls